I learned how to avoid trouble

1

I learned how to avoid trouble

I am Kostas. I was born and raised in Chalandri, which I’d call a middle-class

suburb of Athens. How do I understand my identity? Oh, that’s funny. I don’t

know, it’s very simple. I think I’ve always felt it, without understanding why, since

elementary school. It came very naturally at 12, 13, 14 in junior high. The

realization that I like men… it’s always been there, without even thinking about

it. I never experienced any tragic problems in my life related to my sexuality.

Maybe because the town I grew up in is a nice one, with good schools, and

the people in the surrounding area have a good level of education and high

standard of living in general, no issue ever led to particularly confrontational

situations. So we didn’t have any overt, explicit problems related to that.

I don’t think my friends in school or in my neighbourhood, or my relatives,

“knew” that I was gay. They suspected I was until I was out of school. And this

suspicion caused some trouble. I faced minor bullying, but not serious stuff that

dominated my life. As for bullying, well, I was picked on a lot because of my

glasses when I was a child. I’m 53 years old now. There was this intense bullying

about my glasses, but it was probably a combination of things. I was also a

student in the National Conservatory, and I was one of two children in my

entire middle and high school who went to this conservatory for classical music.

So all of this obviously made me stand out to my peers as a target for petty

bullying who may have understood on some level – even though they couldn’t

be sure – that I was probably gay.

In my community, there was no one else gay and out at the time. Yes, it

affected me, but not very strongly. In my home life, my father was the kind of

man who was interested in keeping trouble out of our little suburb. As long as

there was no trouble, everyone could go about their lives. So many things were

kept invisible, unspoken, not acknowledged. Never in his life – he passed away

about three years ago – he never addressed things in our personal lives, he

2

preferred not to know. Of course, he knew something but wouldn’t

acknowledge it. Any time he found out about personal problems, he never got

involved. Whether it was about me or my sister, he just never really dealt with

our lives, he never opened up. He was rather afraid to address them. Yet, he

never went out of his way to make problems for us.

The problem was my mother. When she started to realize about me, when I

was around 16 to18 years old, she would often cause problems and yell. Not

anything like threatening to kick me out of the house, my mother would never

do that… but more like, just screaming and yelling. It was a pretty typical

situation, I would say… And to think–I was a teenager in the 1980s, and at that

point my mother thought that going to a therapist would make me better, cure

me of homosexuality. So she took me to a psychologist. Of course the

psychologist told her that I wouldn’t get better, because there’s nothing wrong

with me. But the psychology helped me regardless! It helped me find

self-confidence, and by the time I was about 20 years old, I was able to

accept myself, and stop caring what the people around me did and said.

But always, within suburbia, the unspoken message to gays was clear: we can

tolerate you if don’t flaunt it. And I guess that’s how I’ve learned to operate my

whole life. In downtown Athens, it’s a different story. Especially before the

metro, the distance from the suburbs to the center was significant. It took an

hour and a half to get to downtown Athens by bus. This distance allowed me

to be a different person when I was downtown… I could be more free with my

own friends, either from the Conservatory or later on in business, especially the

art business. So I didn’t experience intense bullying, but on the other hand, I

learned how to avoid trouble. When I saw things getting sticky, I would leave. I

didn’t want to get caught up in trouble so I learned how to avoid certain

situations and leave places before things escalated.

3

The only time I didn’t avoid trouble was very recently, three years ago. Even at

my age, and I was outside of a theater of all places…theaters are supposedly

more enlightened places. Well, a man, not an actor, but a theatergoer,

attacked me both verbally and physically. This was the first time I have ever

experienced physical violence. He broke my glasses. He didn’t punch me, it

was more like scratches. I don’t know why, because it was completely

unprovoked. The play was over and the audience was filing out onto the

sidewalk. This man lunged at me directly, using familiar curses like faggot,

asshole, I don’t remember exactly what else. He scratched my face and broke

my glasses. And I still haven’t found out why he attacked me. We weren’t

totally unknown to one another. We weren’t friends, we’ve never even had a

coffee together, but he knows me from around. I know that he is, from what

others have said, something of a troubled person. But he doesn’t belong to any

extreme racist or fascist or Nazi groups or anything like that. I’m really very

curious to hear what he’s going to say in court, what kind of excuse he’s going

to give for himself. He’ll probably say that I have wronged him in some way,

but even if I did do something like that, he should have gone to his lawyer. If I

did something wrong, he could have tried to sue me or something. He’s got a

kind of hatred, an intolerance, inside him. Even though he’s not affiliated with

an organized group. Ultimately, I don’t know why he did it, what his reasons

were, and I don’t know if he really feels that he was acting against all

homosexuals. Maybe he wasn’t. He was against me, personally, and I haven’t

spent too much time sitting down to think through all of that.

The worst part isn’t that he did it. It wasn’t that he broke my glasses, stomping

on them out of rage, and the worst part wasn’t that I was covered in blood

from his scratches. The worst part was afterwards. I went to the closest police

station right away, Omonia – this infamously awful police station in Greece –

with an acquaintance who had witnessed the event. Well, the cops in that

station are who they are. So it’s the worst situation that can exist in Greece. We

know that for a fact. Of course they took my statement. They couldn’t ignore

4

me when I was standing there with blood flowing. And I went the next day on

the advice of a lawyer to take a forensic examination and have it officially

recorded. But two or three days later, when that lawyer tried to obtain the

report from the police station, they wouldn’t give it to her. Eventually she got

the report, she was determined. Three years have passed and the case still

hasn’t been tried yet, but that’s a story for another day. Eventually, I will be

vindicated and put this whole experience behind me.

That was the only time I’ve been overtly attacked. Of course, I’ve heard things

directed toward me on the subway, for example, people out with friends

saying, “Oh look, he’s a faggot,” but I am completely indifferent that kind of

thing. I mean, I won’t engage them, I won’t even respond, because you don’t

know what people are like and you don’t want to escalate anything. But I

think the suburbs have changed too, they have gotten better over the years

and the younger generations are always much better. In my suburb, these

days, there is no issue. All the people of my generation know who I am. They

know all too well that I’m gay, and I don’t face anymore scrutiny than that. My

own classmates, who may have bullied me back in the day, are now

supportive and we can go out and have coffee and have no problems. But it’s

a good suburb. In one of my jobs, in the theater, I do hear things and see

some negative things, but I don’t have any problems.

Obviously, my parents, relatives, the friends of the family in our suburb – there

are so many of them living there – always avoided the subject in conversation,

of course they might have understood that I was different, but they never

would have addressed it directly with me or my parents. Out of politeness, out

of civic courtesy. And if they did broach the subject at all, they were very

vague, saying something like, “He’s different.” They didn’t even say anything

about Stavros Parava, when he was performing in a very flamboyant role. It

was none of their business. So they simply said that he was different. They didn’t

say it contemptuously, though. Obviously they didn’t approve, but I think they

5

didn’t want to get into sensitive situations with a child of their own. Because I

think that in my area, my uncles and my parents’ friends thought of all of us kids

as their kids. So if there’s a difficult topic, we don’t touch it, and it doesn’t exist.

We cover it up nice and tight and don’t talk about it.

Now that I think of it, I can recall one positive incident. One of my many cousins

in the area where I grew up is frighteningly religious. He’s a little younger than

me, and he had five kids because he’s forbidden to use a condom, his wife is

forbidden to have an abortion. He has a child who is profoundly disabled. She

has no arms and no legs. This cousin always treated me coldly and in a very

distant way. He’d say ‘Hello’ and nothing else. For decades, he didn’t want

anything to do with making conversation with me. Never ever ever ever ever

ever. He always kept me at arm’s length. He didn’t want anything to do with

me, not even a hello. When he had the disabled child, many people criticized

him for not terminating the pregnancy. I had been away for two years, so by

the time I met this child she was almost two years old. And I said, “Let me hold

her, but show me how to hold her best, because without arms and without legs

I’m not sure the best way to hold her.” So he does and he asks me, “Does it

bother you that I had a child with these disabilities? Everyone says we should

have had an abortion.” I answered, “Whether or not you should have had an

abortion two years ago is none of my business. Now the child is here. She was

born like this. I, too, was born differently.” Since that day, our relationship has

grown deeper and we have become much closer.

Maybe I can say that’s a good way to grow up, we hid it and didn’t talk about

it. My parents’ and aunts’ generations even today prefer to ignore it. I’ll let

them… they’re 80 years old. There’s no point in throwing it in their faces. But it’s

not easy, even in this nice suburb, with its educated people, to go out holding

hands with my partner. That won’t be possible in my generation. The younger

generations are already doing it. I can see it. I’m just not going to do it in my

suburb, go out hand in hand with my partner. I’ll do it elsewhere, like in

6

downtown Athens, no problem. But in my hometown I want to avoid problems,

avoid trouble, avoid gossip. I’d rather not have that in my life. Even if it means

I’m hiding.

As far as my professional life, I work in two industry and I won’t say that I am

gay in either. Of course some people can tell. I don’t say it directly because I

don’t want to lose clients. I work in tourism, and I would certainly lose jobs,

that’s for sure. If people spontaneously understand it, fine, I’m not going to

deny it anymore…But still, I can’t say it outright. Because business is business

and if I lose a job, we’re all gonna be in trouble.

Now in the theater industry, things are much more relaxed. There are two

components in the theater industry: the television people, who can also

participate in live theater, and then, the rest of the industry. Those who are just

in the theater have no problem, it’s old news. But the people who are on TV,

are afraid of the general public, so they are extremely closeted. Out of all the

big name actors in their 30s, 40s, 50s, 60s who are on TV right now, almost-half

of them are gay, and they don’t say it. Of course, I don’t want to name names

like that myself, it’s not my job to make those kinds of jabs. Let anybody say it

for themselves, if they want to.

There is only one TV actor who says it publicly: Kapoutzidis. There is no other out

TV personality. And still he gets a lot of flak for it, even with his prominence. I

think it’s about the general public. In live theater, there is a pretty narrow

audience. These are people who really love the theatre and don’t care if the

actor is gay. Television is another beast. Especially in Greece, TV is a scary

medium against gays. Scary even today. The way that journalists – real or fake

journalists – address everyday issues in the morning shows and the evening

shows is incredibly anti-gay, even if they pretend in some way to be

gay-friendly. These shows sensationalize rapists, and conflate them with being

gay…which they’re not, these are rapists of girls and women. But the shows

7

build on this assumed connection between the rapists and the sexual perverts

and the gays.

Now, I don’t believe that a TV actor, male or female, will lose their audience by

coming out. Not anymore. Because people don’t really know the actor, it’s just

someone they see on TV. They see him playing a role on TV. The actors are

afraid, but the audience won’t change. Because people will forget about it

and they’ll focus on the role, not the actor. You don’t see an actor next to you,

he’s not your friend, he’s just someone you see on TV.

In Greece, I think our problem is in society, it’s on the streets. It’s a class issue.

One thing is Chalandri, another is Peristeri… or Korydallos. And certain LGBTI

people bear the burden of most of the harassment. The feminine gay guy or

the butch girl… these people are treated worse by society. The alleged gay

man who is macho is more tolerated by society. Anything else, society doesn’t

want to tolerate. So, people who are more visually noticeable have more

pronounced problems. But the street is a reflection of social issues. As are

schools of course. I mean, when you walk down the street and depending on

the area you will or will not face problems… It’s one thing to walk in the heart of

Kifissia, which is one of the wealthiest suburbs, which I don’t think anyone in

there has a problem with gays. The upper class don’t have a problem with gays

either. It’s a different experience to walk around in a working class

neighborhood. Because yes, politically, even the communist suburbs are

anti-gay. In Greece, the communist party is anti-gay, maybe so are all the

communist regimes. I don’t know… Cuba has made progress in this

problem…they had camps for the gays back in the early years.

In general, I think society is better today than it was in the 80s when I was

growing up. There is no comparison. We may have intense Nazis now, but we

had Nazis back then too… we had them just fine. Borides, who is now the

Minister of the Interior, was in the fascist youth organization back then, this

8

business with the axes is nothing new. Things are better today, there’s no

doubt. For one, young people today can talk. We…at least me and many

people of my generation…don’t want to talk. We are afraid to talk. So we don’t

get in trouble with our communities, we don’t want to ruffle feathers, or cause

problems for our own people. On the other hand, the twenty-somethings will

talk to their parents, these parents who are my age. And many of them will

accept their children being gay. Of course I can’t speak for every situation.

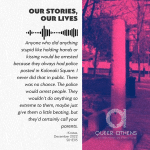

I can remember that in the ’80s, when I first started going out in downtown

Athens, after taking a bus and a taxi from Chalandri, there were only two gay

spots. First, the Pieros rock bar, which had nothing to do with Pieros in Mykonos.

Second, there was the gay discotheque, the Alexander. They were both in

Kolonaki. Well, when we got out of the clubs at 3:00 to 4:00 a.m. on a Friday or

Saturday, and we walked down to Kolonaki Square to find a way home,

anyone who did anything stupid like holding hands or kissing would be arrested

because they always had police posted in Kolonaki Square. I never did that in

public. There was no chance. The police would arrest people. They wouldn’t do

anything so extreme to them, maybe just give them a little beating, but they’d

certainly call your parents. So you might get beaten up and your parents

would be informed, they’d be embarrassed, because our parents didn’t know

what we were up to. Our generation wouldn’t tell. So I avoided this trouble very

nicely and when the police were approaching, I’d blend into groups of straight

people and make small talk with the girls. I wasn’t eager to talk to the guys

because straight guys back that, as soon as they knew someone was gay

they’d likely be ticked off. So I got away with this strategy, but other friends had

been arrested. They were identified, got a little beating, and embarrassed their

parents at home. Well, that was all it took.

We didn’t have the Internet. There were only these two bars in all of Attica.

Nothing else! You chose your music, either rock or disco. So I started out as a

teenager going out to either one of those two places. There were some

9

magazines. And the magazines had personal ads, so we could use them to

meet. We didn’t have cell phones. It was very difficult to communicate. We

wrote letters to post office boxes if we couldn’t receive letters at home. I

couldn’t receive mail at my family home, of course, so I rented the post office

box to send and receive letters. This is within Attica! We could make plans and

make dates by letters, which today seems completely ridiculous, laughable.

Giving your phone number was very tricky, because of course your parents

would likely be the ones to answer the call. If you were lucky enough to have

an older friend, who was 18 and lived alone, maybe you could give out his

phone number. With the help of friends you could start to make things

happen.

There were no other venues aside from these two bars. Of course, there were

outdoor spaces. Pedio tou Areos and Zappeion Park were the known spots.

They were established cruising spots well before ‘89 and the influx of refugees,

at which point it became a more commercial spot. The park is not an easy

place at night. Night is night, and then you have to worry about the police,

plus whatever else can happen in a park. And of course Limanakia, a

consistent spot for who knows how long. Of course, Limanakia is not what it

used to be, now it has bars and restaurants and all that…it’s a completely

different style these days. Okay, that’s why I say nowadays it’s all much easier.

Back then, meeting on the street by chance could be very difficult because

you may be afraid of what people around you would say or do. Even in the

center of Athens! Wellx, now it’s completely different! If you pick someone up

in the center of Athens, it’s easy. Yes, that was the limited gay life we had back

then.

We were trying to meet and get to know friends of friends, trying to befriend a

college student or someone slightly older who had their own place so we

could have a place to hang out. There were a few, because it wasn’t easy for

us Athenians to meet people who had come to the city from the provinces to

10

study. If these are the only options – Friday or Saturday night you can go to one

of two places – well, that’s not much of a gay scene. So for people who didn’t

want to meet in public and hook up, how do you meet people? It’s tough.

How do you meet people? You could wait until summer to go to Mykonos.

Because back then the other islands dind’t have a gay scene yet. So, some

people went to Mykonos. So you had to wait for the summer to have a good

time. But those of us who were, for example me at the National Conservatory

and others at art schools – certainly had better options. That is, there were

always gay art students, art venues, so we could meet more people and get

exposed to more. The fewer gay people you know, the less sex and the fewer

relationships you can have. For those who felt very comfortable cruising and

having sex in the park regularly, great. Good for them. However I never felt

comfortable doing that. Of course I’ve done it from time to time, but it’s always

been awkward for me. And then of course the public bathrooms- they were a

very intense scene in my day. But for me, at least, it’s not a sex environment

that I enjoy.

First of all, I think there were public bathrooms in Syntagma Square, long before

the subway. There were also the toilets in Pedio tou Areos. Oh, and Omonia…

the famous Omonia, of course, but I didn’t even go there. Those are the three

places that had popular cruising bathrooms. There may have been others but I

can’t remember now. There were a lot of people going to those bathrooms in

Syntagma and Omonia and Pedio tou Areos. If I happened to be passing by, I

would ignore the scene even if I got waved at. I don’t like hanging around in

the toilet area. In the park, the signals and the conversation was very easy.

Nothing to it! You’d walk by, see a guy, you shook your head if you didn’t like

him, and walked up to the next guy. Find someone, and you’d tuck away

behind a bush. Or maybe you’d go to a house, if there was a house available.

That wasn’t as common. It was a very easy thing to have sex in the park or in

the bathrooms. There was a convenience to it. Like Limanakia. I guess I liked

that place more. Of course, the beach, in the summer, that was preferred by

11

everyone, in all seasons really. At Limanakia, I don’t know if there was any

danger…and the park… Well, you never know what will happen in a park.

Murders have happened, we’ve known about them since Taktsis’s time.

And there was another area, now that I remember, where you could go

cruising. Solonos high up, near St… what’s the name of the Saint there? Is that

St. Dionysus? The church just before Kolonaki? I think it’s Agios Dionysis. Around

there you could meet people. That was more classy, wasn’t it? Kolonaki, now!

Yeah, I remember that now, yeah. You could meet people there.

Then around ’89 or ’90, something better happened. A bar opened,I don’t even

remember the name of it, on Syngrou Avenue. Nothing to do with the sex work

scene on Syngrou, different type of scene. A nice place with a courtyard and

coffee bar. It had nothing to do with the existing nightlife on Syngrou. This was

the first cafe where we could go to drink coffee, openly as gay people, during

the day.That was great.I remember that. You could have a good time

because, yeah, you sat down, you had a cup of coffee, you could meet

people, you could go with somebody just as a person, not about sex. Just as a

person, drinking coffee and talking, one gay person to another. Then

eventually one or two more opened in Gazi, before the metro was built,

nothing to do with the development that coincided with the metro. Then

came the bars and then the clubs and so on, the big ones, but before all that

there were a couple of simple bars in Gazi. I don’t even remember their names

anymore. Until 2000… I think it’s after 2000 that the big change happens. And

suddenly too many things open up, too many places. The whole Gazi scene

emerged. Intense. Now we had gay spaces, lots of them.That solved a lot of

problems, but not everything. But after 1998, 2000, gay life grew enormously.

Before then, I didn’t even know what gay life could mean. How could I,

sending my little postcards?!

12

There’s no comparison. It’s a better time today. No question! There were

attacks and so on back then. Let’s not pretend. It’s not a new problem now,

these kinds of attacks are more well known because we can write about them

on the internet. All kinds, not just LGBTQ hate crimes. Violence against women,

abuse, murder, rape, it was all there. We just didn’t have the internet to write it

all down and call it out. So if a woman was being beaten up, she didn’t share

it. Her mother would tell her to stay where she was, it’s okay. A little beating

ain’t bad. Things have always happened like this.

I wish I was 20 years old right now. Not because I’m afraid of getting older, not

at all! But I wish I was 20 years old now, so I could have had the experience of

being raised by parents who belong to the generation that are now in their

fifties, so I could grow up inside the society we have now, this society that even

has civil partnership for gay couples in Greece. So I could be able to do things

that weren’t an option for me when I was young. I wish I could have a young

gay person’s life now – of course I do have this kind of life now, but I didn’t have

it when I was young. I wish I had been young during a time when I could have

walked the streets comfortably with a partner, and have the Internet and

dating apps at my disposal. Many people say that mobile phones are bad for

society, but I think those things are so important. For everyone’s personal life as

well. It’s much better, I live much better now as a gay man. For so many

reasons. And I’m not nostalgic for anything from the 80s.

If we manage to eliminate the extreme phenomena in society, the racism, the

fascism, I think we can set up a better situation. Many people may point out all

the problems we have today. Yes, that’s true, but we are much better off than

we were, and we have to keep working towards improvement. The

homophobia that they say exists today, yes, it exists, but it doesn’t compare to

the magnitude of homophobia we faced in the 90s and 80s and 70s. There is

no comparison for That. In the past 40, 50 years, the situation has gotten a

13

whole lot better. The strides that have been made in the 70 years since the ’50s

are incredible, compared to 2000 years back. I’m not saying we’re done, of

course there are another 200 steps, but I think everyone will agree that young

people, they’re living better now. We had a hard time in ’80s and ’90s, and a

gay man in the ’50s lived even more tragically than that.

Of course, in any country, there is an urban and rural divide. Athens and

Thessaloniki are one thing, and villages in Pindos are another. But just as Athens

has taken 100 steps forward in the past 40-50 years, so did the provinces.. They

are behind the city, but they are further ahead than they were 40 years ago.

That’s what I’m saying.

Well, yes, the serious steps started in the twenty-first century, let’s say the last 20

years and especially in the last 10, that is after the crisis. That is my view.

Suddenly Greek society had to deal with terrible economic problems that it

hadn’t experienced since the 1950s. When people were drowning in debt and

losing houses and committing suicide, who cared iif the person next door was

gay? You stop worrying about your neighbor’s personal business because the

other next door neighbor killed himself over his mortgage debt and the other

neighbor had no electricity in the winter and was freezing to death. People

died of cold in those years, let’s not forget it. Those two or three years of the first

austerity measures, they were serious issues and people stopped gossiping so

much about who is gay. So all of a sudden society went forward.

Yes, in the last ten years. What is ten years? What was going on when I was

born? That is, when Taktsis, the great Taktsis, who was already a well-known

writer, was killed because he dressed as a woman… Today, okay, this kind of

murder and violence still happens, but not as frequently. No, no, we’re not safe,

and that’s why I share a lot of myself in professional settings, so I don’t lose

customers, so I don’t lose my livelihood. Despite that, I feel in my heart that

today it’s not like it was 20 or 30 or 40 years ago. In 10 years, we have made

14

monstrous steps for Greece, especially in Athens and Thessaloniki followed by

smaller, slower changes in the villages. did it above all, followed by Thessaloniki

and then the villages. Yes, okay, okay, the villages are behind, always. They

follow further behind, they’ve always been further behind though, why in Britain

and Italy, in America aren’t their villages further behind? That goes without

saying.

There’s no comparison. I’m terribly happy that we live in this era, despite its

crookedness. Things are better than they were 20 or 40 years ago.Or even 60

years or before that when there were concentration camps. That’s why I’m very

grateful.